Is Medication Right for Me?

Sometimes, you feel like something just isn’t right. You feel sad and it’s not passing, and you don’t want to get out of bed anymore. You have anxiety to the point where it’s getting hard to function. You may find yourself wondering if you need help and what that help looks like.

You may ask yourself: Do I need medication?

And this can be a scary question.

In this article, I will review the following aspects of using medication to treat mental health issues:

What is the history of using medication to treat mental illness?

Richardson Complex. Photo Credit: Kevin Hayes

Modern psychopharmacology began in 1950 with the discovery of chlorpromazine, also known as Thorazine. Prior to 1950, the only drugs available served to sedate and calm agitated patients, without treating the underlying illness. With the discovery of chlorpromazine and similar medications, psychiatrists found that they could calm agitated and anxious patients without too much sedation. This constituted a meaningful improvement in treatment, which also allowed many patients to avoid much more drastic interventions such as electroconvulsive therapy and lobotomy.

In the same decade, other medication classes were discovered: antidepressants and benzodiazepines. All these medications generated enormous sales, while also impacting everyday practice and the conception of mental illness. Prior to the 1950s, psychiatry was dominated by the theories of psychoanalysis, in which mental illness was understood as reflecting a mix of biological, social, and psychological factors. Treatment was aimed at modifying those factors, especially through talk therapy. Psychiatry was also largely administered in state hospitals.

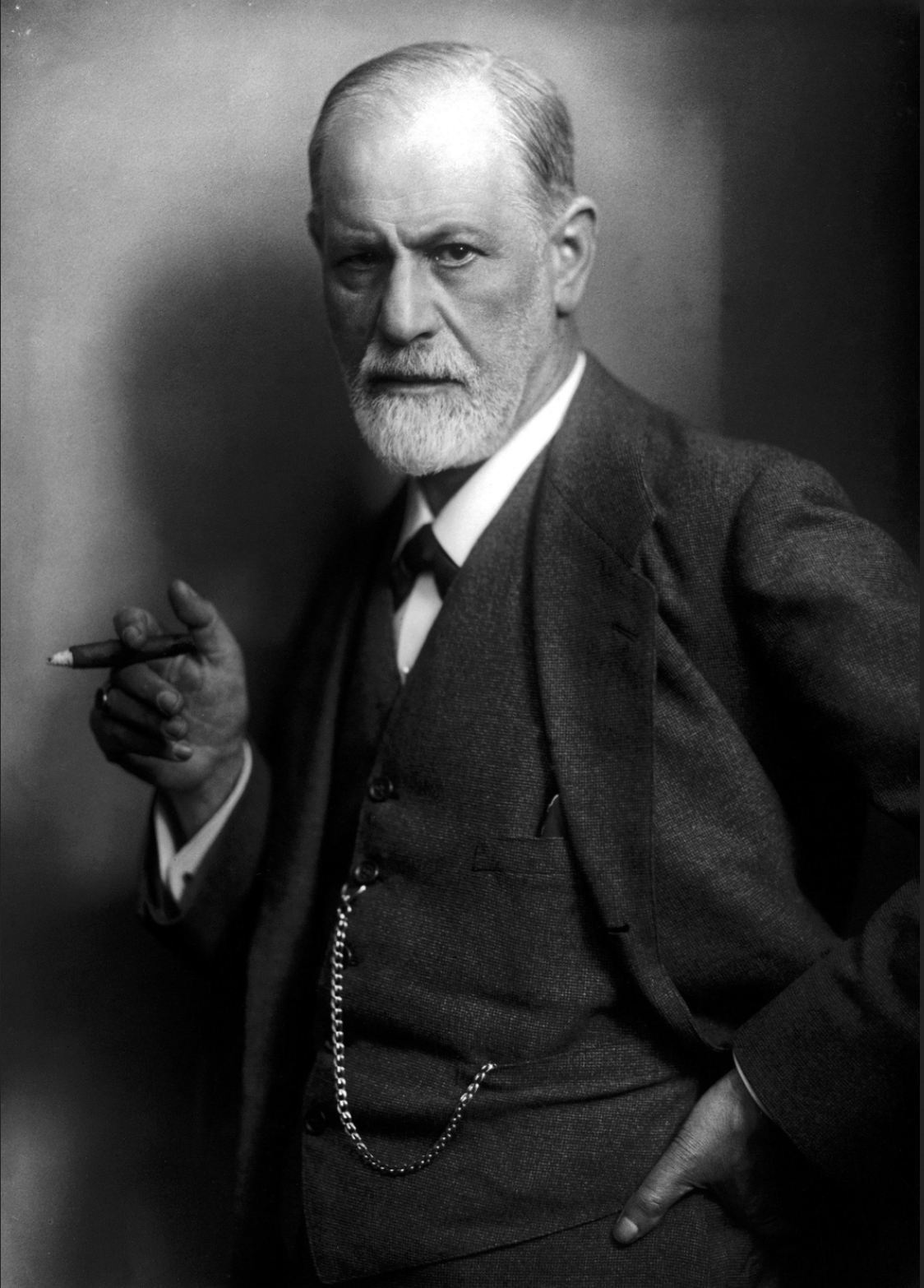

Sigmund Freud, Founder of Psychoanalysis

With the discovery of medications that alleviated certain symptoms of mental illness, the conception of mental illness began to shift. The mechanism of action of medication was used to infer the mechanism of disease, even though medication ultimately did not prove to be any type of magic bullet nor were the inferred mechanisms adequately explanatory. The measurement of mental illness also changed. Diseases were defined by the symptoms that could be measured in a randomized-control trial and treated by medications. Disease was thus separated from its sociocultural and psychological context, and outcomes separated from the meanings that patients and doctors found in the patient’s life, treatment, and doctor-patient relationship.

Photo Credit: Buddhi Kumar Shrestha

Psychiatry continued to evolve alongside new discoveries in medication and social changes, notably policy changes that moved to decrease the number of patients in state hospitals. The latter lead to increasingly shorter hospital stays and rising admission rates, which gave psychiatrists less time and resources to spend on patients. Medication thus evolved from being seen as an adjunctive treatment to facilitate psychotherapeutic work, especially through psychotherapy, to a primary treatment tool used to rapidly alleviate symptoms and hasten discharge. It is worth nothing that medication did not solve the problems faced by severely mentally ill patients, now living outside of state institutions. Instead, many patients previously living in state institutions became homeless or incarcerated.

Photo Credit: Naomi August

In the 1970s and 1980s, there emerged many of the medications which are considered first line treatment today: atypical antipsychotics (Clozapine, Risperdal, etc.) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Prozac, Zoloft, Paxil, Celexa, Lexapro, etc., also known as SSRIs). Atypical antipsychotics were promoted as being more effective with less side effects than the first generation of antipsychotic drugs, though this was ultimately not borne out in research nor in clinical practice except for Clozapine, whose use is limited by potentially fatal side effects. SSRIs, meanwhile, had a much more benign side effect profile than older antidepressants and could thus be used to treat patients with milder depressions, often in primary care settings.

Photo Credit: Michiel1972

Today, medications are widely prescribed for various mental illnesses, and the disease model of mental illness that came along with pharmacological interventions, research and marketing has become foundational to modern psychiatry. This may be at the detriment of a more rounded understanding of mental illness which includes social and psychological factors, which themselves cannot be treated by medication.

Should I take medication?

Given the history of pharmacology in the context of a changing social, political, economic, and medical landscape, you may wonder if medication is helpful and if you should take it.

Firstly, any psychiatric intervention must start with a thorough psychiatric assessment. Though definitive psychiatric diagnoses are best made over time, a comprehensive assessment is essential to get a sense of the underlying disorder to be treated, as well as the likelihood of response to various treatment interventions. Once you are aware of your diagnosis, your treatment options, and your likelihood of a positive response with each one, you can make an informed decision about how you’d like to proceed.

Photo Credit: Johny Georgiadis

You should also be aware that the impact of a medication depends on how you feel about it and how you feel about your provider. If, for example, you have seen a loved one respond positively to a medication, and you feel comfortable and positive with your provider, you are more likely to respond well to medication. If, on the other hand, you’ve seen medications fail repeatedly in yourself and others, or you aren’t happy with your provider, or you feel that taking medication is shameful or a sign of failure, you are more likely to have a negative reaction to medication.

Photo Credit: National Cancer Institute

If you do have negative feelings about medication, it’s important to talk about them with your provider, regardless of what you ultimately choose to do. Addressing negative feelings helps you to give yourself maximum options as well as self-understanding and compassion.

What are the risks and benefits of medication?

Photo Credit: Towfiqu Barbhuiya

This depends on the specific medication and its class, as well as your own medical background. Please feel free to discuss this in depth with your provider to make an informed decision.

Generally speaking, many patients who seek treatment from a psychiatrist or primary care provider for symptoms of depression, anxiety, OCD and trauma will first be prescribed an SSRI, or selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Common side effects of this drug class include digestive upset, headache, sweating, feelings of restlessness or agitation, vivid dreams, decreased libido and delayed orgasm. Other notable side effects include suicidal thoughts especially in those under 25 and discontinuation syndrome, which are flu-like symptoms that occur when one stops taking the medication.

For more severe mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or depression that has not adequately responded to an SSRI alone, patients may need to take antipsychotics and/or mood stabilizers. Antipsychotics carry much more significant side effects including sedation, movement disorders, substantial weight gain, metabolic syndrome, sexual dysfunction, postural hypotension, cardiac arrythymia and sudden cardiac death; while mood stabilizers also carry significant side effects, depending on the particular medication. These side effects are weighed against the severity of the underlying illness. When left untreated, severe mental illnesses cause major disability and potentially death.

Many patients have tried benzodiazepine medication (Valium, Klonipin, Xanax). Patients often find that benzodiazepines provide immediate and effective relief of panic, anxiety, insomnia and agitation, and they often find this relief to be more noticeable than that provided by other medication classes. Unfortunately, benzodiazepines carry significant risks and side effects, the most significant of which is addiction and life-threatening withdrawal. Like opiate medication, benzodiazepines must be used only when necessary and as little as possible because continued use often creates more harm than benefit.

What is it like to take medication?

Photo Credit: Karl Frederickson

Every person responds differently to medication. In my experience, there are some common themes in what people describe:

SSRI’s really do help.

The majority of patients that I’ve treated have experienced improvement in their underlying symptoms when they take an SSRI, whether those symptoms relate to depression, anxiety, OCD or trauma. Oftentimes, patients seek treatment because they feel that their symptoms have reached a point where they need more drastic intervention. I have seen SSRI’s provide the improvement that patients need to get out of that particularly bad place which led them to seek care.

SSRI’s aren’t a magic bullet.

While many people find their symptoms to be substantially and meaningfully improved by an SSRI, I have rarely heard nor seen cases where the underlying condition being fully resolved with an SSRI. However, many people do feel satisfied with the improvements that they’ve seen.

SSRI side effects are usually not deal-breakers, but they can still be significant.

Many side effects resolve over time. Among those that don’t, sexual side effects are often the most problematic. There are interventions for those side effects, which should definitely be discussed with your provider.

Medication classes used to treat severe mental illness, such as antipsychotics and mood stabilizers, do reduce target symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions.

However, they are not able to reduce all the symptoms of the underlying condition, including very disabling symptoms such as cognitive impairment. Also, the side effect burden is substantial, and many patients do not like how the medication makes them feel. However, many patients do take the medication despite the side effects because of their awareness of how disabled they become without it.

Benzodiazepines often feel like “the only thing that helps”, but they carry huge risks.

The effect of benzodiazepines and, indeed, the mechanism of action, is actually similar to that of taking a shot of alcohol. It has an immediate impact and significantly reduces distress. However, just like a shot of alcohol, it really isn’t a good long-term solution, and many patients are better off never trying them in the first place.

What are my other options?

Blossom Center for Integrative Psychiatry Office

Medication addresses one aspect of mental illness (the chemical/biological), and it addresses it in a specific way. However, there are many other components to mental illness, each of which can be addressed with different interventions:

Psychological factors

To me, this is actually the biggest component of any mental illness, and it is addressed with talk therapy. Sometimes, therapy alone is effective; other times, medication and therapy together are the optimal treatment.

Image Credit: Priscilla Du Preez

Other medical conditions

A number of medical conditions can cause mental health symptoms, such as anemia, thyroid imbalance, and COVID, just to name a few. These should be worked up and addressed by the appropriate medical provider.

Photo Credit: Abby Anaday

Nutrition

Today’s food landscape contains a significant amount of processed and refined foods, sugar, and toxins, all of which negatively impact mental health. Also, some of the prevailing wisdom of healthy eating may inadvertently lead people to forgo a necessary amount of protein and fat. It is important to optimize your nutrition to ensure that your brain works at its best, which is something that you can discuss with a medical provider.

Photo Credit: Anna Pelzer

Conclusion

The complex decision to take medication reflects the complexities of psychiatry itself. The “right” decision is ultimately going to be made with the right provider – one who can help you navigate and make sense of the risks and benefits, as well as your own feelings. The “right” decision is the one that is right for you.

If you are interested in becoming a patient at BCIP to discuss your specific situation and questions about medication, please feel free to schedule a free 15-minute consultation.

Sources:

1.) Braslow JT, Marder SR. History of psychopharmacology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2019;15(1):25-50.

2.) Požgain I, Požgain Z, Degmečić D. Placebo and nocebo effect: a mini-review. Psychiatr Danub. 2014 Jun;26(2):100-7. PMID: 24909245.

3.) Side effects - Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Ssris). nhs.uk.

4.) Muench J, Hamer AM. Adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. afp. 2010;81(5):617-622.

5.) Edinoff AN, Nix CA, Hollier J, Sagrera CE, Delacroix BM, Abubakar T, Cornett EM, Kaye AM, Kaye AD. Benzodiazepines: Uses, Dangers, and Clinical Considerations. Neurol Int. 2021 Nov 10;13(4):594-607. doi: 10.3390/neurolint13040059. PMID: 34842811; PMCID: PMC8629021.